Ameimse a commencé la lecture de Les abysses par Rivers Solomon

Les abysses de Rivers Solomon

Lors du commerce triangulaire des esclaves, quand une femme tombait enceinte sur un vaisseau négrier, elle était jetée à la …

Un compte bookwyrm pour y partager/recenser diverses lectures : - des romans de littératures de l'imaginaire (science-fiction, fantasy, fantastique). Lus principalement en VF, parfois en VO anglophone. - quelques écrits adoptant des perspectives critiques pouvant être féministes, décoloniales, écologiques... - possiblement à l'occasion des livres d'histoire.

Sur mastodon, je suis par là : social.sciences.re/@ameimse

Ce lien ouvre une nouvelle fenêtre

Lors du commerce triangulaire des esclaves, quand une femme tombait enceinte sur un vaisseau négrier, elle était jetée à la …

Tant de récits de l’histoire de la Terre sont prisonniers du fantasme de la beauté des premiers mots et des premières armes, de la beauté des premières armes comme mots, et vice versa. L’outil, l’arme, le mot. Le mot qui s’est fait chair à l’image du dieu céleste. C’est ça Anthropos ! C’est une histoire tragique qui ne compte qu’un seul véritable acteur, un seul véritable faiseur de monde : le héros. C’est l’histoire de l’Homme en chasseur cherchant à tuer et à ramener son effroyable butin. C’est le récit tranchant, acéré et combatif d’une action qui repousse au-delà du supportable la souffrance de la passivité gluante, terrestre et pourrie. Dans ce genre d’histoire viriloïde, tout autre protagoniste est accessoire, support, domaine, espace pour l’intrigue ou proie. Sans importance aucune, son rôle n’est pas de voyager ou d’engendrer, mais de se trouver sur le passage, d’être un obstacle à franchir, ou encore une voie, un conduit. Que ses beaux mots et ses belles armes n’aient aucune valeur sans un sac, un récipient ou un filet pour les contenir, c’est bien la dernière chose que le héros veut savoir. Nul aventurier, toutefois, ne devrait quitter la maison sans un sac. Mais comment une écharpe, un pot ou une bouteille entrent-ils tout à coup dans l’histoire ? Comment ces humbles choses permettent-elles à l’histoire de continuer ? Ou – ce qui est peut-être pire pour le héros – comment ces objets concaves, évidés, ces trous dans l’Être, engendrent-ils, dès le départ, des histoires riches, plus insolites, plus denses, des histoires inconvenantes, des histoires sans conclusion, des histoires où le chasseur a sa place, mais dont il n’est pas, ou n’a pas été, le sujet, lui, l’humain qui se fait tout seul, la machine à faire l’humain dans l’histoire ? La courbure légère d’une coquille qui contient juste un peu d’eau, juste quelques graines à donner ou à recevoir, suggère des histoires de devenir-avec, d’induction réciproque et d’espèces compagnes dont la vie et la mort n’ont pas pour rôle de mettre un point final aux récits, d’achever les mondes en formation. Avec une coquille et un filet, devenir humain, devenir humus, devenir Terrien, prend une tout autre forme : la forme sinueuse, qui avance tel un crotal, du devenir-avec.

— Vivre avec le trouble de Donna J. Haraway (Page 259)

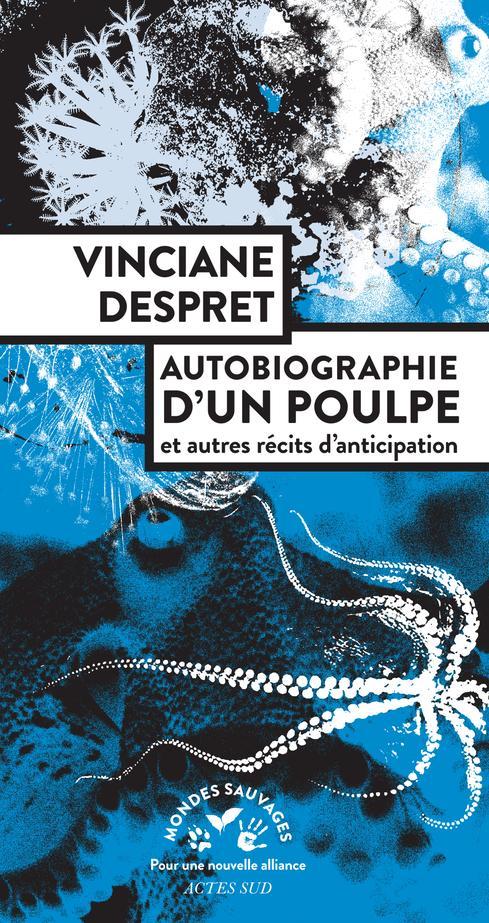

Dans la continuité d"Autobiographie d'un poulpe", j'ai plongé dans "Vivre avec le trouble" (qui m'attendait depuis fort longtemps). La manière dont Vinciane Despret et Donna Haraway dialoguent (et dont leurs oeuvres résonnent entre elles) est particulièrement stimulante. Le tout aussi en référence à l'oeuvre science-fictionnelle d'Ursula Le Guin. Et justement, dans ce passage cité, Donna Haraway propose sa réception et prolonge la fameuse théorie de la fiction-panier d'Ursula Le Guin.

Dans la continuité d"Autobiographie d'un poulpe", j'ai plongé dans "Vivre avec le trouble" (qui m'attendait depuis fort longtemps). La manière dont Vinciane Despret et Donna Haraway dialoguent (et dont leurs oeuvres résonnent entre elles) est particulièrement stimulante. Le tout aussi en référence à l'oeuvre science-fictionnelle d'Ursula Le Guin. Et justement, dans ce passage cité, Donna Haraway propose sa réception et prolonge la fameuse théorie de la fiction-panier d'Ursula Le Guin.

@Armavica@bookwyrm.social Encore merci pour la recommandation :)

Une nouvelle série. Totalement indépendante de la précédente The Expanse. Où comment se comportent et survivent des humains lorsqu'ils sont enlevés et mis en captivité, par une espèce non humaine, afin d'évaluer leur utilité. De la difficulté de (re)devenir un animal comme les autres parmi des milliers d'espèces provenant de milliers de mondes. A la capacité des humains à trouver une voie entre résister et se soumettre, pour leur survie et la survie de leur espèce. Au plus près des personnages, hommes comme femmes, humain ou pas. Très réussi selon moi, il faut résister aux premiers chapitres sur les intrigues purement humaines.

Une nouvelle série. Totalement indépendante de la précédente The Expanse. Où comment se comportent et survivent des humains lorsqu'ils sont enlevés et mis en captivité, par une espèce non humaine, afin d'évaluer leur utilité. De la difficulté de (re)devenir un animal comme les autres parmi des milliers d'espèces provenant de milliers de mondes. A la capacité des humains à trouver une voie entre résister et se soumettre, pour leur survie et la survie de leur espèce. Au plus près des personnages, hommes comme femmes, humain ou pas. Très réussi selon moi, il faut résister aux premiers chapitres sur les intrigues purement humaines.

William Morris est un artiste, peintre, éditeur, préraphaélite, fondateur de l'Arts and crafts. On lui doit, entre autres, de somptueux motifs de papiers peints, dont l'un est en couverture. Il fût également militant socialiste, dans son acception première, et, donc, également écrivain.

John Ball, prêtre, disciple de Wycliff, il fût, avec Wat Tyler, le guide des Lollards et de la révolte paysanne en Angleterre en 1380-1381. Il dira :

Quand Adam bêchait et Ève filait, où était alors le noble ?

Phrase reprise par les insurgés paysans de 1525 en Allemagne.

Le titre du présent ouvrage est à double sens, un rêve de Morris sur John Ball ou bien un rêve de John Ball.

Morris se rêve à rencontrer Ball au début de l'insurrection. Et il discute ardemment avec lui sur la révolte, son devenir, l'avènement de la société dans laquelle …

William Morris est un artiste, peintre, éditeur, préraphaélite, fondateur de l'Arts and crafts. On lui doit, entre autres, de somptueux motifs de papiers peints, dont l'un est en couverture. Il fût également militant socialiste, dans son acception première, et, donc, également écrivain.

John Ball, prêtre, disciple de Wycliff, il fût, avec Wat Tyler, le guide des Lollards et de la révolte paysanne en Angleterre en 1380-1381. Il dira :

Quand Adam bêchait et Ève filait, où était alors le noble ?

Phrase reprise par les insurgés paysans de 1525 en Allemagne.

Le titre du présent ouvrage est à double sens, un rêve de Morris sur John Ball ou bien un rêve de John Ball.

Morris se rêve à rencontrer Ball au début de l'insurrection. Et il discute ardemment avec lui sur la révolte, son devenir, l'avènement de la société dans laquelle il vit, toujours constituée d'oppressions, d'aliénations. Il essaie d'expliquer pourquoi la révolte, si elle est vouée à l'échec, n'en est pas moins juste et nécessaire pour l'avenir.

La harangue imaginée de Ball est prenante.

La préface est de William Blanc, auteur de plusieurs ouvrages sur l'histoire de la vision de la société médiévale. Il donne le contexte historique et politique de Morris qui mythifie la société médiévale, par rejet de la société capitaliste en pleine révolution industrielle.

4 tomes, une longue vie qui les traverse. Ces romans parlent de vie et de mort, d'amour et de haine, de regrets et de culpabilité. C'est aussi une vaste réflexion sur la responsabilité (ce qui n'est pas très original), mais aussi sur ce que signifie le futur (ce qui l'est un peu plus), dans un monde fondé sur le pouvoir des mots... Bref, c'était beau et prenant.

4 tomes, une longue vie qui les traverse. Ces romans parlent de vie et de mort, d'amour et de haine, de regrets et de culpabilité. C'est aussi une vaste réflexion sur la responsabilité (ce qui n'est pas très original), mais aussi sur ce que signifie le futur (ce qui l'est un peu plus), dans un monde fondé sur le pouvoir des mots... Bref, c'était beau et prenant.

Un court livre, lu suite au partage de lecture de @Armavica@bookwyrm.social.

Il m'a tour à tour passionné, dérouté, stimulé, interrogé... Sa restitution elle-même est difficile, car c'est un livre qui investit un registre un peu à part, défiant diverses catégories pré-établies, y compris littéraires, jouant entre fiction, science et science-fiction. Cela donne donc une lecture qui perturbe les réflexes et les grilles préalablement intériorisées par les lecteurices pour appréhender un texte qui mêle, voire défie, les genres.

Face à un tel format, j'ai d'abord trouvé aussi fascinante que stimulante la démarche entreprise par l'autrice : une esquisse, en mobilisant un soubassement imaginaire, de désanthropisation du regard scientifique, questionnant les réflexes intériorisés, mais aussi les méthodes qui fondent la scientificité contemporaine. Le texte surfe en quelque sorte sur une ligne de crête. D'une part, on assiste à une déstabilisation/remise en cause de catégories et un renouvellement de méthodes, …

Un court livre, lu suite au partage de lecture de @Armavica@bookwyrm.social.

Il m'a tour à tour passionné, dérouté, stimulé, interrogé... Sa restitution elle-même est difficile, car c'est un livre qui investit un registre un peu à part, défiant diverses catégories pré-établies, y compris littéraires, jouant entre fiction, science et science-fiction. Cela donne donc une lecture qui perturbe les réflexes et les grilles préalablement intériorisées par les lecteurices pour appréhender un texte qui mêle, voire défie, les genres.

Face à un tel format, j'ai d'abord trouvé aussi fascinante que stimulante la démarche entreprise par l'autrice : une esquisse, en mobilisant un soubassement imaginaire, de désanthropisation du regard scientifique, questionnant les réflexes intériorisés, mais aussi les méthodes qui fondent la scientificité contemporaine. Le texte surfe en quelque sorte sur une ligne de crête. D'une part, on assiste à une déstabilisation/remise en cause de catégories et un renouvellement de méthodes, aboutissant à réévaluer la place dans les savoirs de divers êtres vivants et l'appréciation humaine de leurs créations. D'autre part, la mise en lumière des dynamiques conduisant à la constitution d'une nouvelle discipline scientifique n'en est pas moins chargée d'ambivalences. Si la discipline nouvelle essaie de faire exploser certaines hiérarchies (se positionnant contre un savoir anthropocentré), on n'en assiste pas moins à la reconduction d'autres hiérarchies : ainsi, une forme de désanthropisation de la conception de l'écriture n'en voit pas moins se perpétuer des références à l'oralité et à son "champ étroit". J'ai eu le sentiment que l'autrice s'attachait à mettre en scène les ambiguïtés des révolutions scientifiques et des conditions par lesquelles un savoir reconnu comme scientifiquement légitime pouvait être produit. Dans une telle perspective, le dernier texte, justement celui qui donne son titre à l'ensemble, "Autobiographie d'un poulpe", constitue le dernier temps de l'exploration-démonstration de l'autrice : on y suit, sous un format épistolaire, le trajet d'une narratrice qui, depuis un cadre institutionnel scientifique futur, s'en affranchit progressivement. Un autre rapport au monde, au vivant, au temps, à l'existant... est envisagé, en restituant une pleine subjectivité aux poulpes. C'est un texte que j'ai trouvé particulièrement fort : il aborde frontalement l'extinction de masse en cours dans notre présent, évoquant des enjeux très actuels pour les lecteurices, tout en investissant une tonalité plus incarnée et émotionnelle, qui tranche avec les compte-rendus distants des précédents textes.

Au final, un livre très stimulant, qui m'a beaucoup questionné. J'ai désormais plusieurs autres livres écrits ou co-écrits par Vinciane Despret qui m'attendent sur ma PàL ! :)

Lire Les Années de Virginia Woolf a été pour moi comme feuilleter un album de famille où les images se superposent, incomplètes, parfois floues, mais chargées d’une vérité intime. Le roman suit la famille Pargiter à travers plusieurs décennies, de la fin du XIXe siècle aux années 1930. Pourtant, il ne s’agit pas d’une saga traditionnelle : Woolf s’attache moins aux événements qu’aux sensations, aux changements imperceptibles qui façonnent la vie.

Dès les premières pages, j’ai senti que le temps était le personnage central. Les saisons, la lumière, les bruits de la rue, tout devient indicateur de ce qui change et de ce qui reste. Chaque chapitre est comme une fenêtre ouverte sur un moment précis, sans jamais tout dévoiler. Ce qui m’a frappé, c’est cette capacité à dire l’essentiel par l’ellipse, à suggérer plutôt qu’à expliquer.

Je me suis attaché aux Pargiter non pas pour leurs actions, …

Lire Les Années de Virginia Woolf a été pour moi comme feuilleter un album de famille où les images se superposent, incomplètes, parfois floues, mais chargées d’une vérité intime. Le roman suit la famille Pargiter à travers plusieurs décennies, de la fin du XIXe siècle aux années 1930. Pourtant, il ne s’agit pas d’une saga traditionnelle : Woolf s’attache moins aux événements qu’aux sensations, aux changements imperceptibles qui façonnent la vie.

Dès les premières pages, j’ai senti que le temps était le personnage central. Les saisons, la lumière, les bruits de la rue, tout devient indicateur de ce qui change et de ce qui reste. Chaque chapitre est comme une fenêtre ouverte sur un moment précis, sans jamais tout dévoiler. Ce qui m’a frappé, c’est cette capacité à dire l’essentiel par l’ellipse, à suggérer plutôt qu’à expliquer.

Je me suis attaché aux Pargiter non pas pour leurs actions, mais pour leurs silences, leurs gestes minuscules. Woolf capte la manière dont les ambitions, les amours et les regrets se transforment avec l’âge. Et moi, en lisant, j’ai senti ce mélange d’élan et de nostalgie que donne la conscience du temps qui passe.

Les Années m’a appris que l’histoire d’une vie n’est pas faite seulement de grands moments, mais aussi d’instants fugaces : un rayon de soleil sur une tasse de thé, une conversation interrompue, un parfum porté par le vent. Quand j’ai refermé le livre, j’avais l’impression d’avoir vécu aux côtés des Pargiter, et peut-être aussi d’avoir observé ma propre vie à travers ce prisme délicat et impitoyable qu’est le regard de Virginia Woolf.

Dans le Vieux Pays, le peuple souffre sous la domination du Trône de la Lune. L'empereur et ses fils monstrueux …

Un roman de fantasy qui se lit comme un polar. Il faut dire que Noon le sorcier tient plus de Sherlock Holmes que de Gandalf. D’ailleurs, c’est son assistant Yors qui est le narrateur de l’histoire, un peu à la manière du Dr Watson.

Noon enquête grâce à sa faculté à lire les signes magiques et à naviguer dans un monde parallèle peuplé de morts, de créatures magiques et d’autres sorciers. J’ai bien aimé l’idée des signes anodins du monde réel qui correspondent à une réalité sous-jacente dans le monde du soleil noir.

C’est un livre tout public : le style est simple et accessible, le niveau de violence est à peu près celui d’un Agatha Christie, pas de sujets glauques ni de sous-texte subversif. Si on rajoute à ça les nombreuses illustrations, on pourrait croire qu’il s’agit d’un roman jeunesse (mais apparemment non) .

L’ensemble est …

Un roman de fantasy qui se lit comme un polar. Il faut dire que Noon le sorcier tient plus de Sherlock Holmes que de Gandalf. D’ailleurs, c’est son assistant Yors qui est le narrateur de l’histoire, un peu à la manière du Dr Watson.

Noon enquête grâce à sa faculté à lire les signes magiques et à naviguer dans un monde parallèle peuplé de morts, de créatures magiques et d’autres sorciers. J’ai bien aimé l’idée des signes anodins du monde réel qui correspondent à une réalité sous-jacente dans le monde du soleil noir.

C’est un livre tout public : le style est simple et accessible, le niveau de violence est à peu près celui d’un Agatha Christie, pas de sujets glauques ni de sous-texte subversif. Si on rajoute à ça les nombreuses illustrations, on pourrait croire qu’il s’agit d’un roman jeunesse (mais apparemment non) .

L’ensemble est sympathique et se lit vite. Ça fait toujours plaisir de voir des auteurs francophones s’emparer d’un genre d’ordinaire réservé aux anglo-saxons. Mais le côté très consensuel m’empêche d'être vraiment enthousiasmé pas ce livre.

C’est un roman assez court qui se déroule dans des pays imaginaires en guerre. Il propose une réflexion très intéressante sur le fonctionnement d’une anarchie. C’est un roman agréable et addictif. #mastolivre #vendredilecture #fantasy #steampunk #anarchie

C’est un roman assez court qui se déroule dans des pays imaginaires en guerre. Il propose une réflexion très intéressante sur le fonctionnement d’une anarchie. C’est un roman agréable et addictif. #mastolivre #vendredilecture #fantasy #steampunk #anarchie

Dans le Vieux Pays, le peuple souffre sous la domination du Trône de la Lune. L'empereur et ses fils monstrueux …

Connaissez-vous la poésie vibratoire des araignées ? l’architecture sacrée des wombats ? les aphorismes éphémères des poulpes ? Bienvenue dans …

D'abord, il faut écrire. Pour écrire, on a besoin d'un peu d'argent et d'une chambre / d'un lieu / d'une pièce (au choix) à soi. Pleins de textes ne sont jamais écrits par leur autrice est trop occupée à biberonner, langer, nettoyer, rassurer, ranger, cuisiner, turbiner, plaire, flatter, stimuler, encourager, coudre, accoucher, réconforter, épiler, lessiver, répondre, câliner, s'imposer, balayer, satisfaire, éviter, soigner, retrouver ses esprits, serpiller, exciter, se défendre, épousseter, habiller, s'habiller, lisser, nourrir, transitionner, produire, s'excuser, excuser, reproduire, sourire, riposter, guérir, s'échapper, servir, fabriquer, cultiver, pétrir, cicatriser, fuir, usiner, se débrouiller, éduquer, réparer, se réparer, s'interrompre parce que ça déborde, ça crie, ça demande, ça exige, ça mate, ça bloque, ça insiste, ça force. Ça laisse tout de suite moins de temps pour écrire. Ça c'est là un premier processus de masculinisation, qui s'articule bien sûr avec d'autres processus comme le blanchiment, l'embourgeoisement, l'hétérosexualisation.

— Sur les bouts de la langue de Noémie Grunenwald (Page 62)

Je sais que dans cet ouvrage j'utilise parfois des termes dans les définir. C'est un choix que je fais et que j'assume. D'habitude, c'est toujours aux autres différents de se définir, de se situer, d'exposer leur « parcours », leurs « particuliarités », leurs « origines », leurs « orientations ». On en demande rarement autant aux normaux : les hommes n'ont pas un point de vue masculin, ils ont un point de vue, les blanc·hes ne sont pas blanc·hes, iels sont sans couleur, les hétérosexuel·les n'ont pas d'orientation sexuelle, iels sont naturel·les. Alors pourquoi je devrais définir les relations butch/fem quand jamais personne ne définit les modalités du couple hétérosexuel ? Pour les mêmes raisons, je parle de moi sans me définir clairement. Sans nommer les cicatrices qui marquent mon corps. Sans référencer mes hontes ni mes fiertés. Les femmes sont souvent reléguées à la figuration. Au mieux célébrées pour ce qu'elles sont. Pour ce qu'elles sont supposées être. Pour l'image que les hommes se font d'elles. Jamais pour ce qu'elles font. Je ne veux pas nommer qui je suis car je veux parler de ce que je fais. Ce que je suis est important, oui, mais ça ne m'intéresse pas. Ce qui m'intéresse, c'est ce que j'en fais. J'aime ce que je fais. Je crois en ce que je fais. Je veux qu'on me parle de ce que je fais. Pas de qui je suis.

— Sur les bouts de la langue de Noémie Grunenwald (Page 73 - 74)